What's an API?

What McDonalds and Lyft have in common

The TL;DR

Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) are like drive-thru windows, but in code: they take inputs and give you predictable outputs.

At its core, an API is a bunch of code that takes an input and gives you an output

Most modern applications (like Excel) are a bunch of APIs working together

Sometimes, companies will make parts of their APIs publicly available, like Twitter or Google Maps

APIs are one of the more confusing concepts in software, because they can mean a lot of different things

APIs power most of modern software development, and are a key part of being able to talk intelligently about code. So read this!

What’s an API (theoretically)?

If you want to understand APIs, there’s an important separation to make: there’s the technical definition of an API, and then there’s how people actually use the concept in conversation. They’re very different, which is why this stuff can get so confusing. Let’s tackle the technical definition first.

An API is a group of logic that takes a specific input and gives you a specific output. A few examples:

If you give the Google Maps API an address as an input, it gives you back that address’s lat / long coordinates as an output

If you give the Javascript Array.Sort API a group of numbers as an input, it sorts those numbers as an output

If you give the Lyft Driver API a start and finish address as an input, it finds the best driver as an output (I’m guessing)

When engineers build modules of code to do specific things, they clearly define what inputs those modules take and what outputs they produce: that’s all an API really is. When you give an API a bunch of inputs to get the outputs you want, it’s called calling the API. Like calling your grandma.

Inputs

An API will usually tell you exactly what kind of input it takes. If you tried putting your name into the Google Maps API as an input, that wouldn’t work very well; it’s designed to do a very specific task (translate address to coordinates) and henceforth it only works with very specific types of data. Some APIs will get really into the weeds on inputs, and might ask you to format that address in a specific way.

Outputs

Just like with inputs, APIs give you really specific outputs. Assuming you give the Google Maps API the right input (an address), it will always give you back coordinates in the exact same format. There’s also very specific error handling: if the API can’t find coordinates for the address you put it, it will tell you exactly why.

That’s all of the technical, theoretical stuff.

⛓ Related Concepts ⛓

It’s hard to separate anything that talks about APIs from how you actually call those APIs: we’ll cover the architecture of APIs (REST, gRPC, HTTP requests) in some other posts.

⛓ Related Concepts ⛓

Your favorite apps are just collections of APIs

The most empowering thing to understand about modern software is that your favorite apps are just a bunch of APIs with a pretty face on top of them called a frontend. Most apps you use are built on this frontend / backend paradigm.

The backend

Companies start by building APIs for all of the important things that users are going to need to do in their app. For Gmail, Google started with APIs that receive, show, send, and forward emails; but those are all called through code. These APIs, and the logic for when they get used and how, is the application’s backend. It’s like what’s going on under the car hood. If you’re heard of a backend engineer, it’s a developer who’s working mostly on these internals.

The frontend

All of those backend APIs are only usable through code, which isn’t really something you want to deal with to check email on your iPhone. That’s why companies build frontends for their apps: graphical user interfaces that make apps pretty and usable without having to write code. Here’s how that works in Gmail:

Your inbox shows rows of emails and subject lines: the frontend is taking that backend email data and formatting it nicely

You can click on the star icon to flag an email: on the backend, that’s triggering a “mark email as flagged” API

Most interactions on the frontend get translated into an API call on the backend, and that’s application software 101. Once I started to understand this model, it was easier to understand how developers actually use “API” in conversation.

What’s an API (practically)?

In practice, I’ve found that people use “API” in three different contexts, and they all mean different things. In theory, though, they’re all the same and fit the definition we worked through. They’re all the same, but different.

Internal company APIs

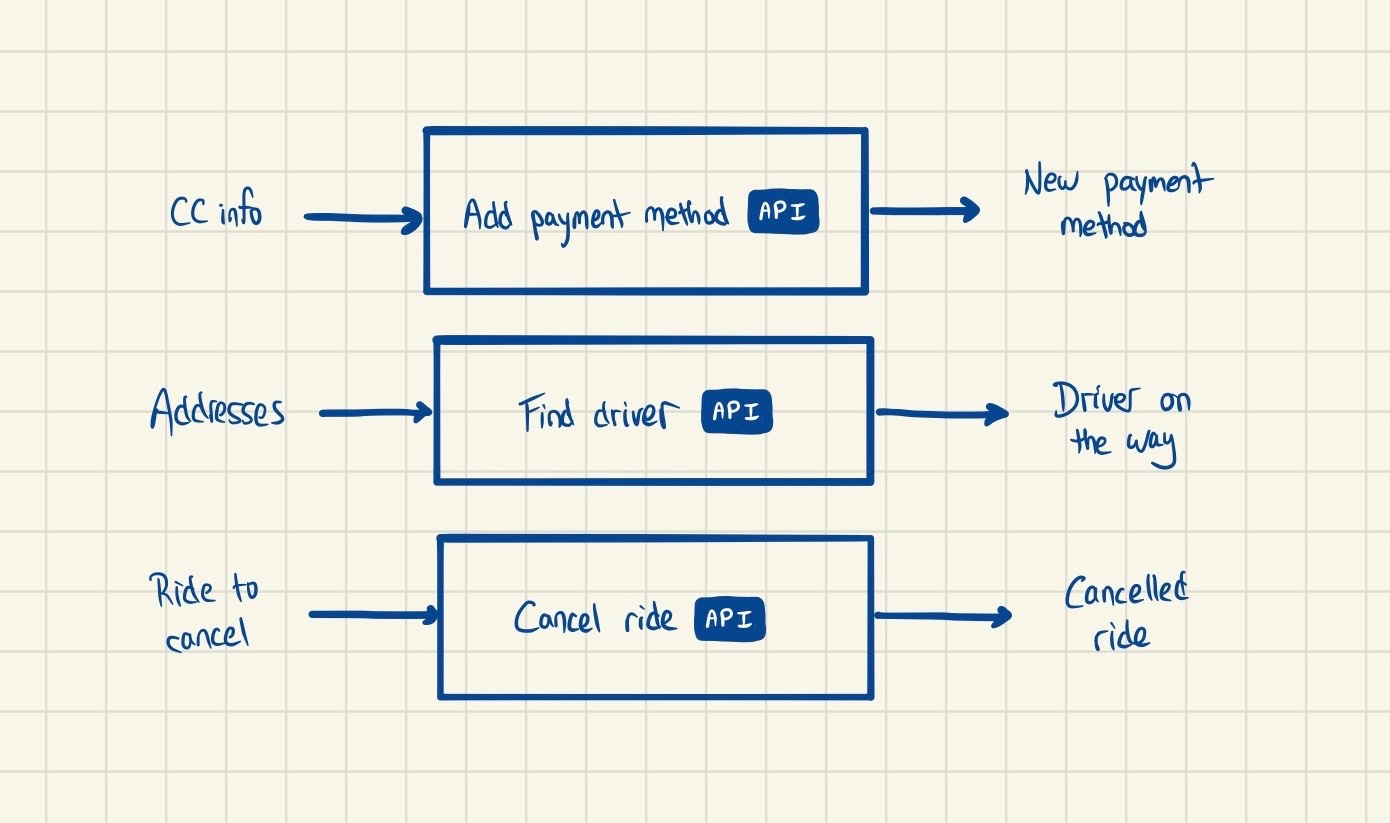

When companies build their applications, they design them as a group of interacting APIs. The easiest example to understand is Lyft (or Uber, if you’re evil. kidding, relax). There are a few things you might want to do in the Lyft app, and they all trigger different APIs behind the scenes.

This pattern holds for almost any app you use: actions that you take in the app will trigger internal company APIs that actually do the work to get your request fulfilled. Internal company APIs are also layered: even though there’s probably a broad “book a ride” API, there are a bunch of smaller APIs under that hood that get it done: find a driver, book the driver, verify credit card, communicate with users, etc.

Public APIs

None of those Lyft APIs are publicly available: they’re just the way that Lyft actually provides their service to you on the backend. But sometimes, companies will make a few of their APIs available, and give you instructions on how to use them. A great example is the Twitter API.

Normally, you’d use the Twitter app, which makes a bunch of API calls to internal Twitter APIs like show feed, send reply, and search (this is what we just spoke about: frontend and backend). But you can also call those APIs yourself, with code, outside of the Twitter app. For example, there’s a get user timeline API that you can use to see a user’s timeline (their tweets) – that API returns those tweets in JSON, which is a special text format.

Now if you’re wondering who the hell cares, it’s because these kinds of public APIs let people build apps on top of Twitter. There’s some really basic stuff, like this school project I did that gets tweets about NYU and analyzes their sentiment, but there’s also some pretty advanced stuff like Flock, which lets you search your followers.

Code interfaces

The first two types of APIs that we just looked at are functional – they usually accomplish something that’s practical and easy to understand, like giving you coordinates or booking a ride. But developers also use “API” to refer to much lower level inputs and outputs, like functions in code. (this is the type of API that took me the longest to understand)

A good example is Javascript’s array.sort() method. It’s an API that takes a list of numbers or letters as an input, and then sorts them and gives them back to you as an output. There are other APIs related to arrays, like for adding (array.push) and removing (array.pop) things, filtering (array.filter), and getting an array’s size (array.length). You use these when you’re writing in Javascript.

🚨 Confusion Alert 🚨

It’s not always going to be clear what exactly people are talking about when APIs come up, especially because developers use the word for a ton of different things. If you’re confused, just ask! Chances are the answer will fit into one of these three categories.

🚨 Confusion Alert 🚨

APIs in conversation

“We’re still figuring out what the API is going to look like, but it should get you what you need”

We’re still deciding exactly what the inputs and outputs of this part of the application are going to be, but it’s probably going to serve your use case either way.

“You can use the Twitter API to get that data into your app”

Twitter’s public API lets you get the data you need programmatically so you can integrate it into your application.

“The API keeps giving me this weird auth error that I can’t fix”

When I try to make API calls, it needs me to login with my credentials but I can’t seem to get that done.

“I built an API that lets you find the 10 closest taco trucks near you at any time”

A future we can all look forward to.

Terms and concepts covered

APIInputs, outputsAPI callsPublic APIFrontendBackendFurther reading

Over the past 5 years or so, the idea of building your application purely as a series of interacting APIs has gotten much more popular, and it’s called microservices

There are a bunch of different ways to work with public APIs in practice, and some even work through your browser

How engineers decide which APIs to build, how they should interact, and when they get called is exactly what software architecture is